Dear Internet: I Am Not A Witch

Dear Internet: I Am Not A Witch

“The victim was an insane old woman from the parish of Loth…who was condemned to death…for the usual crimes of bewitching pigs and poultry, and, worst of all, for having transformed her daughter into a pony and had her shod by the Devil…The story goes that, the morning being chilly, she warmed her hands at ‘the bonnie fire,’ as she called it, while the preparations for her murder were being completed. Apparently she did not realise her situation, and was probably in her dotage.”

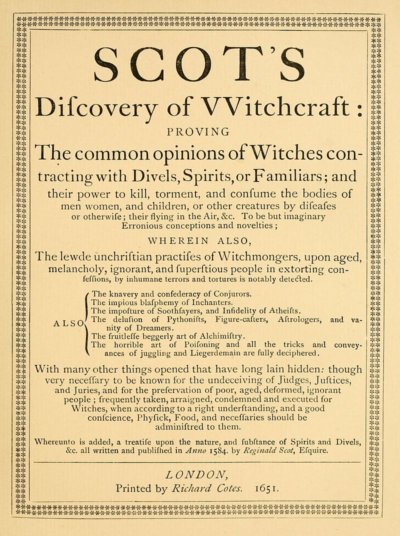

There was a time when the things we did not understand, we condemned as sorcery. People who were different from us were a threat from the supernatural realm, like the senile woman burned at the stake in 1722 in Scotland. Her daughter had club feet, evidence — in the minds of their neighbors — that the younger woman had been transformed into a horse by her mother and ridden into the woods for a visit with Satan. More threatening still were people who did things we could not understand. The first book on conjuring tricks in English, Reginald Scot’s 1584 The Discoverie of Witchcraft, was written to prove that performing magicians were not in league with dark powers.

432 years later I found myself being accused of being allied with dark spiritual powers for a magic trick I performed on TV.

The premise of the show is simple: the magician performs live for Penn & Teller and the bad boys of magic try to figure out how the trick is done. They then communicate the secret to the performer in a way that, hopefully for the conjuror, the audience cannot follow.

This not only gives the show a unique hook, it ingeniously sidesteps the major challenge of presenting magic on TV. The power of magic is that it happens live, right in front of you, without camera tricks, helpful edits, or the use of actors as fake audience members. Increasingly, one famous magician (ok, Criss Angel) has relied so heavily, and so obviously, on fake TV magic that it undercuts the credibility of any magic presented on television.

By having two people in the room who are experts, and who are staking their reputation on being able to see through the trick presented, you know that the magic you see on your screen is what you would experience if you were in the room live.

Magic has a rich literature and history. Developing new magic is a conversation that takes place across centuries; often varying, building on, and tinkering with approaches used by past magicians in new ways to create increasingly compelling live experiences for audiences.

Penn & Teller, along with their team of outstanding magicians Johnny Thompson and Michael Close (who assist in writing the “bust” portion of the segment — where the magician’s secret is revealed), use the names of these past performers — or the names of tricks that are similar that have been published in the literature of magic — to code the secret of the trick to the act.

In my case, one of the principles involved in the act came from a trick that used the word “devil” in its name. Partly to communicate that secret, and partly as tongue-in-cheek praise for the set (at least, I like to pretend it was), Penn coded that part of the secret by saying “there is some work of the devil here.”

Penn, understanding — I’m sure — how this could be misinterpreted, was very careful to preface the comment by saying “Penn & Teller don’t believe in the supernatural.”

Nonetheless, very quickly, a small extremist sect which maintains that the holocaust is a hoax (in a post with this lovely disclaimer: “we are not ‘anti-Semitic’ and we desire the conversion and eternal happiness of all Jews…and we work to expose Jewish domination and evil Jewish enterprises in the world”) posted my video as an example of modern magicians being in league with supernatural evil.

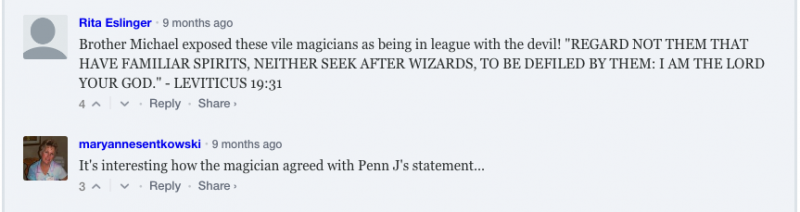

I’m not going to link to the article — they don’t deserve more traffic — but here are relevant screenshots along with comments (both comments on the entry about me, and on other entries about magicians being in league with spirits):

I want to be as clear as I can be (and I’m shocked that this even needs to be said): performing magicians are not in league with dark powers. If we do something that seems utterly unexplainable, it is only because we’ve spent an absurd, unreasonable, amount of time obsessing over how to create the most convincing illusions possible.

Just because you cannot understand something, does not make it the work of Satan, more often it is the work of an anti-social kid with obsessive tendencies and way too much time on his hands.

Indeed, the only thing that makes magic interesting is that it is a work of human artifice. Were it real, it would be — as illusion designer and magic historian Jim Steinmeyer puts it in his book Device and Illusion — “something you put in your toaster.”

There is a kind of artistry in effective deception. When you swear something is one thing, but it is another, it is often the result of hours of painstaking attention to detail. Hours of observing how we naturally move, how we perceive what’s around us, how we come to conclusions. Yet deception, in nearly every other context, is unethical.

Magic is the ethical celebration of the artistry of deception. Ethical because, in the words of the ingenious vaudeville magician Karl Germain “The magician is the most honest of all professionals. He first promises to deceive you, and then he does.”

More importantly, magic connects us to a part of human experience that has been dulled by contemporary culture. We live in a world where we can get the answer to almost any question by reaching into our pocket and giving our smartphones a few taps. This gives us the delusion that we have all the answers.

It is damn hard — in the comfort of that delusion — for us to feel something basic to human experience: wonder. At its highest level, and it is rare, the experience of magic is the pin that pops the balloon of “I know it all.” It brings us dramatically and suddenly to feeling wonder. I believe no other creative discipline provides this experience.

It’s high time we moved past the superstitions that led us to burn our neighbors in the middle ages. If a magician leaves you convinced of something that you know isn’t real, it is a reminder of the limitations of our perception (and ought to lead us to wonder where else we may be being deceived); but it most certainly is not the work of evil spirits who have decided to take up show business.

The Best is Yet to come!

407.900.3831 | NCM@NCMarsh.com

One Response to Dear Internet: I Am Not A Witch